Current exhibition: „Paris, Königstein, Berlin. Louise Rösler (1907-1993)“ from March 22 to August 25, 2024

Guided tours in English

Thu, 16.5., 18.7., both at 4 pm

Overview tour through the current exhibition for adults in English language

Cost: 4 € (plus admission)

Paris, Königstein, Berlin. Louise Rösler (1907–1993)

The Giersch Museum of Frankfurt’s Goethe University is presenting an outstanding twentieth century artist in Louise Rösler, who has yet to be discovered by a wider audience. She was born in Berlin in 1907, and this is the first major presentation of her diverse work in a retrospective, bringing together over 160 exhibits from all Rösler’s artistic periods. She worked as an artist from the 1920s until shortly before her death in 1993.

Rösler came from a family of artists, and travelled extensively through southern Europe after completing her training in Munich, Berlin, and Paris. Back in Berlin as from 1933, she focused on the big city as a subject – a recurring theme in her work throughout her life. Rösler worked figuratively until the 1930s. After moving to Königstein im Taunus due to the war in 1943, she developed a more abstract, freer style emphasizing colour and form as sensual elements and combining them to create dynamic visual worlds. She returned to Berlin in 1959.

The exhibition illustrates the artist’s significance and shows her rich oeuvre in chronological and thematic order: it includes paintings, collages, coloured pencil and felt-tip pen works, watercolours, gouaches, pastels and prints. Louise Rösler’s unwavering, passionate determination to be an artist is impressive – as is the heterogeneous profusion of her works, which are striking in their individuality and independence.

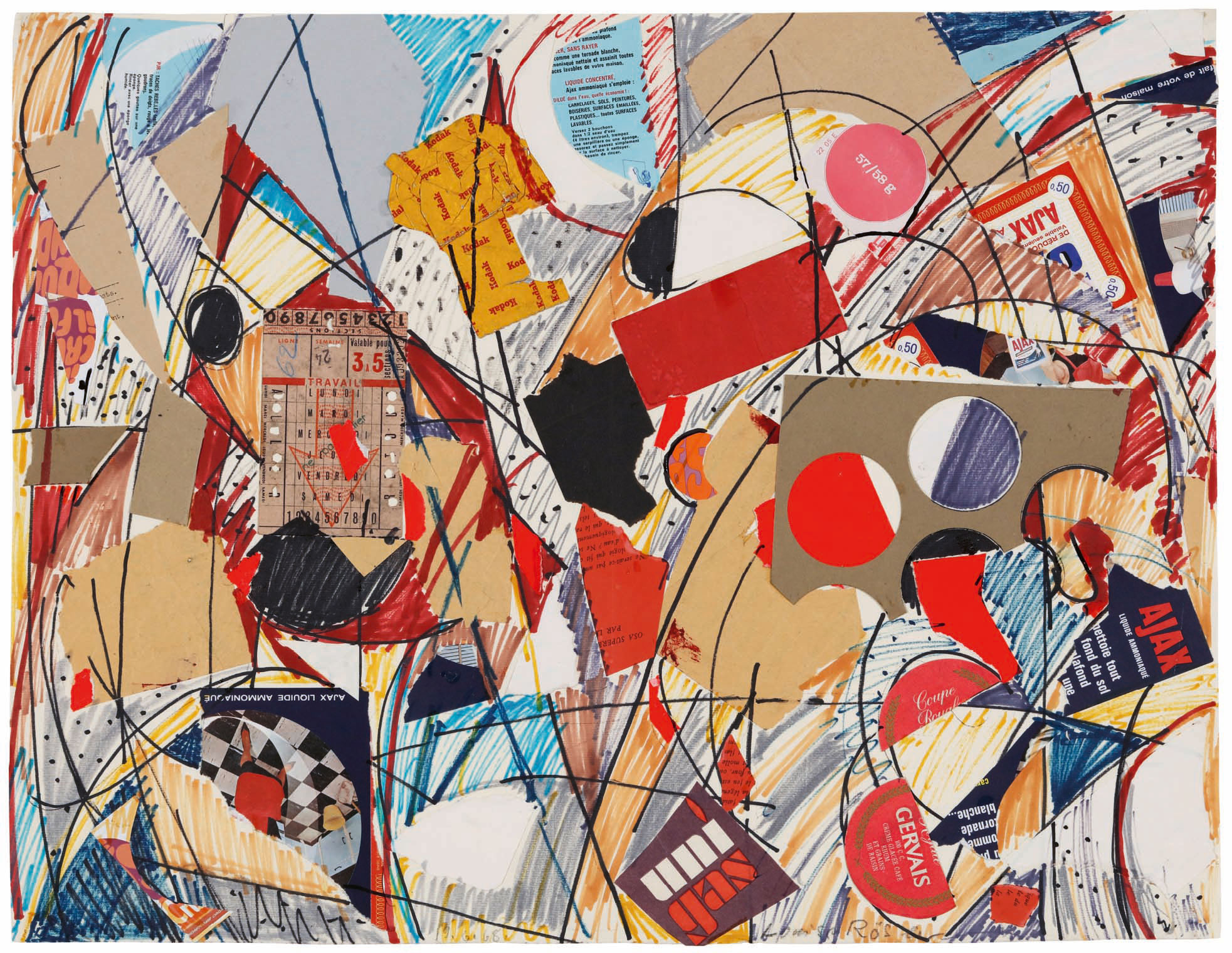

One exhibition theme is the artist’s stand-alone handling of her materials, manifest in both small and large formats and expressed in the medium of collage in particular. Here, Rösler took up the urban not only as a motif but also in her choice of materials: she supplemented her works with found objects from everyday urban life, including paper and packaging picked up on the streets; in later decades, she also incorporated sculptural objects made from wood, metal, plastic and other materials.

Texts about the exibition

Biography of Louise Rösler

1907 Born in Berlin on 8th October, the daughter of artist couple Oda Hardt-Rösler and Waldemar Rösler.

1923 Attendance at Hans Hofmann School of Fine Art in Munich, founded in 1915.

1925/26 Study of painting in Karl Hofer’s class at the Vereinigte Staatsschulen für freie und angewandte Kunst (Combined State Schools of Fine and Applied Art) in Berlin.

1927–1932 Resident in Paris, thought to have attended the Académie Moderne to study under Fernand Léger for a short time. Numerous study trips through southern France, Spain and Italy. Participation in exhibitions at the Berlin Secession and the Prussian Academy of Arts in Berlin.

1933 Return to Berlin. Marriage to painter Walter Kröhnke.

1937–1939 [?] Studio exhibitions for her closest circle.

1939 Birth and death of her son Alexander. Walter Kröhnke is drafted into army service.

1940 Birth of her daughter Anka.

1943 Destruction of the studio apartment in bombing, loss of the majority of previously made works. Evacuation to Falkenstein, later to Königstein im Taunus.

1944 Walter Kröhnke goes missing on the Eastern Front. Birth and death of her son Andreas.

1945/46 Return to work as an artist. First participation in exhibitions after the Second World War.

1950 First solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Düsseldorf, also showing works by Walter Kröhnke.

1959 Return to Berlin.

1968 Several months staying in Paris.

1990 Honorary award from the Berlin Senate Department of Cultural Affairs.

From 1991 Due to illness, she lives with her daughter Anka in Hamburg; continuing work as an artist.

1993 25th June, death in Hamburg.

Big-city fascination: Paris, Berlin

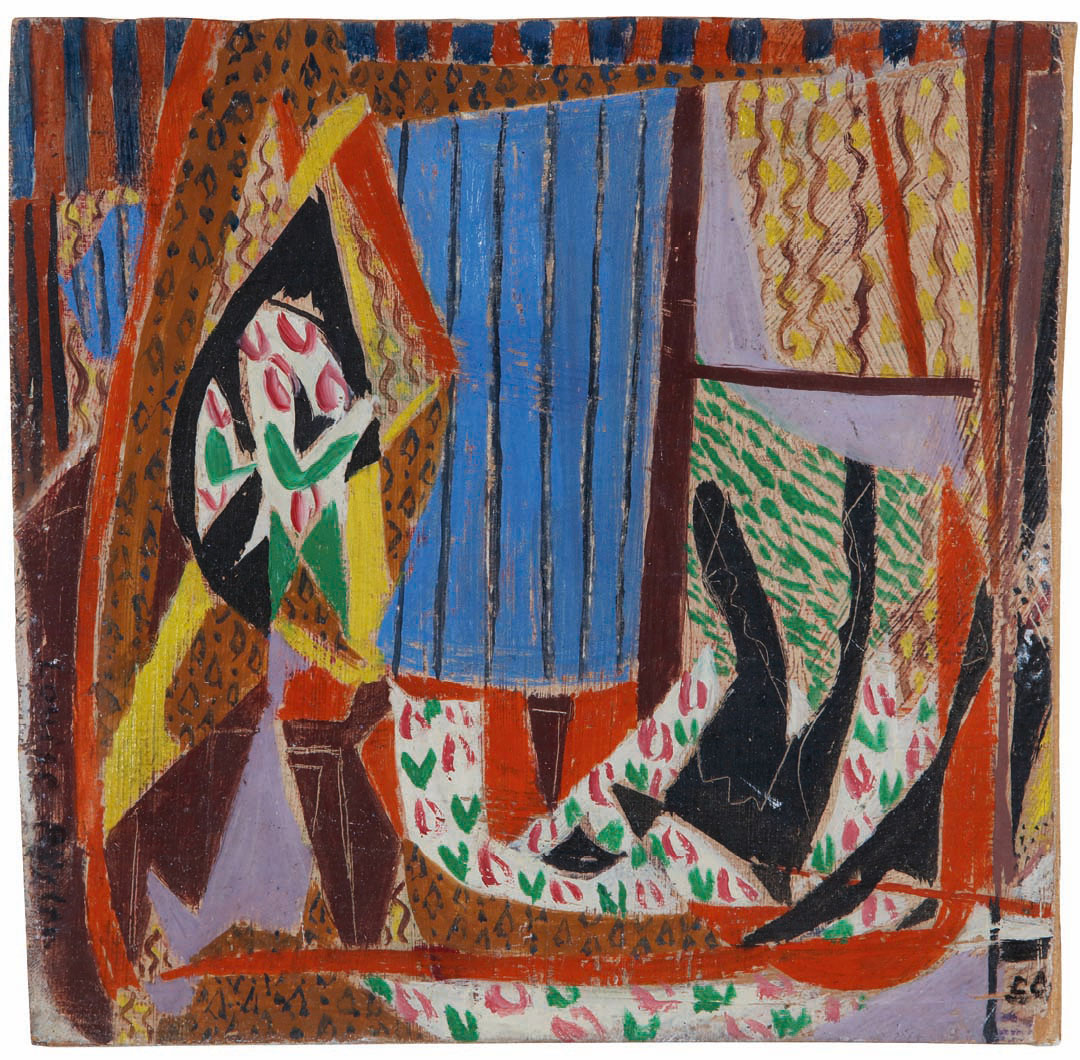

After her artistic training, Louise Rösler spent several years in the art metropolis Paris, which had a powerful influence on her. The painting Mein Pariser Zimmer explores this lifelong place of longing. The artist’s engagement with the works of Henri Matisse is obvious from the decorative formal arrangement of the loose dotted and linear structures.

Extensive travel through southern Europe also made an enduring impact on the young artist. Landscapes and architectural views created face-to-face with her motifs, such as Hotel in Südfrankreich (Cagnes-sur-Mer), show the influence of the French avant-garde, particularly of Paul Cézanne.

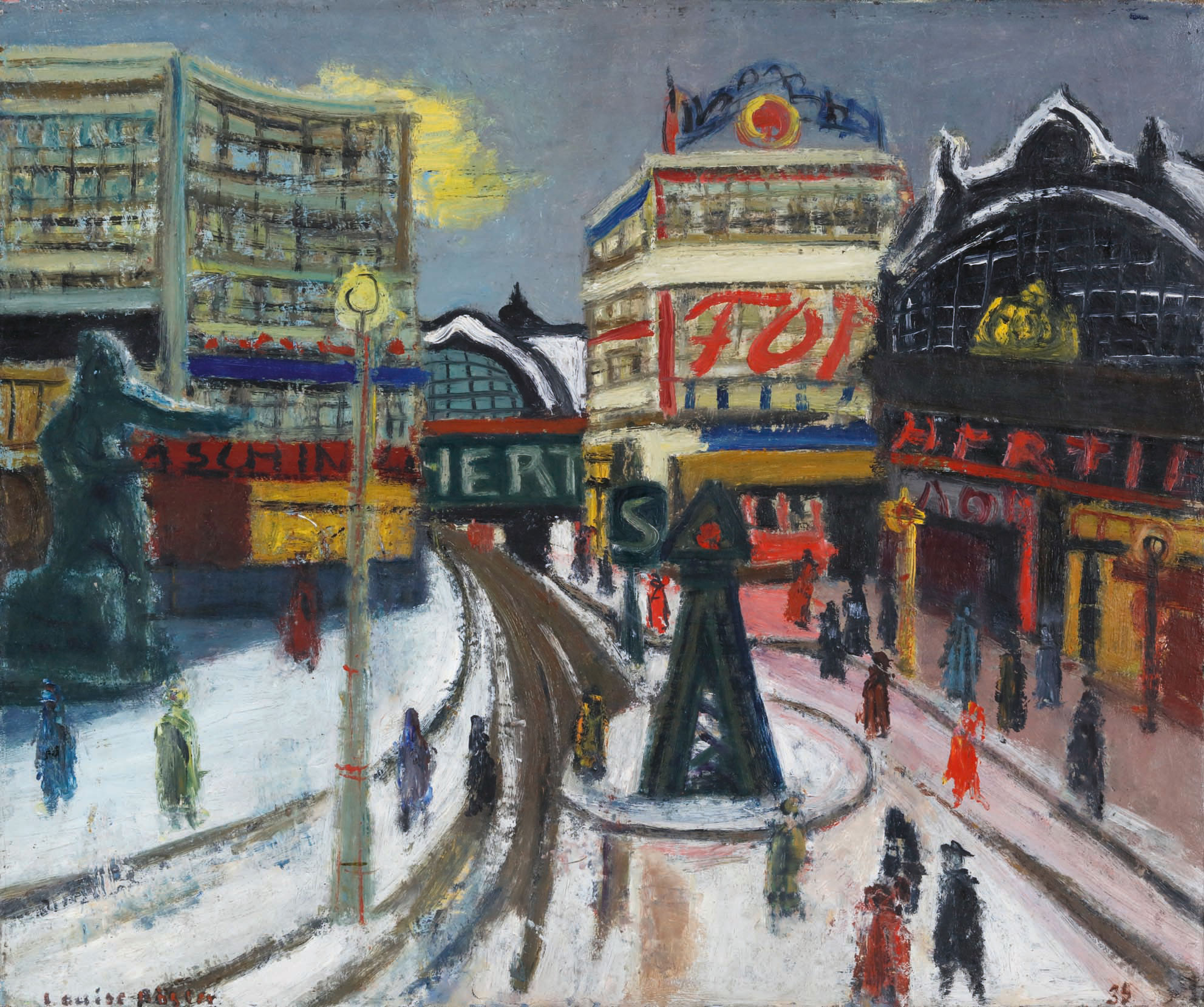

Following her return to Berlin in 1933, Rösler turned to the subject of the modern city in her painting. Urban life with its abundance of visual stimuli – colours, shapes, light and movement – fascinated the artist hugely throughout her life: “My main subject is the big city – and of course, that means the streets – but sometimes also train stations, cafés, etc.,” she said, looking back. The Berlin cityscapes of the 1930s are figurative throughout. The subjective gaze of a strolling flâneur enabled Rösler to collect impressions that she then distilled into paintings in her studio. The resulting views of the city depict prominent squares and sights such as Alexanderplatz, but unidentifiable streets as well. Lettering often appears on shop fronts or advertising boards, and sometimes only fragments can be made out: a reference to the fleeting, fragmentary nature of the primary impression. Towards the end of the 1930s, Rösler’s paintings became increasingly rigorous in their form, the composition and brushstrokes developing in a more linear, harder manner.

Letter pictures and burnt paintings

The beginning of the Second World War in 1939 brought Rösler’s work as an artist almost to a standstill. Her husband Walter Kröhnke was drafted into the Wehrmacht. She herself was living in precarious circumstances with her daughter, who was born in 1940. There was no time for creative work. She produced only sketches of cityscapes, which she had already included in her letters to Walter Kröhnke in the pre-war period. The artist later recalled: “Towards the end of the thirties, I was producing fewer and fewer paintings, and as from 1939 I produced none at all for six years, apart from the small letter pictures I sent to my husband from 1939 to 1944, after he was drafted into the Wehrmacht. […] He sent them all straight back, so that they wouldn’t get lost. Most were views of the places we had visited together.”

In November 1943, a bombing raid totally razed the family’s studio flat in Berlin. Apart from a few works that had been stored away, Louise Rösler’s and Walter Kröhnke’s previous artwork was destroyed. Fortunately, however, photographs of the lost paintings have survived, providing an insight into Rösler’s extensive pre-war work. At the same time, they highlight the yawning gap in the artist’s surviving œuvre.

Precarious new start in Königstein im Taunus

Louise Rösler was forced to leave Berlin with her daughter in 1943. She first found accommodation in Falkenstein, and then in Königstein im Taunus. Her husband had been missing on the Eastern Front since 1944. Despite these difficult circumstances, Rösler managed to resume her artistic production after the war ended. Initially, she created works on paper under provisional conditions. Rösler also designed playing cards and illustrations to generate additional income.

She described her first true painting after the war, Die Prozession (1946/47), as “painted on half a cupboard wall, a key work from 1946”. The artist broke new ground with this piece: Her compositions were moving further and further away from representational depiction. She condensed the pictorial elements, which she regarded as equal in value, into a small-scale, two-dimensional visual structure. Formally, Rösler was particularly interested in Italian Futurism during this period.

Although motifs from the big city or nature provided Rösler with external stimulus, these works created from memory are primarily rhythmic events of colour and form. They are especially captivating due to their luminous coloration. Significantly, the artist’s difficult personal life and the oppressive circumstances of the post-war years are not visible here. Instead, she retained her receptivity to visual stimuli even in everyday experience. The sensual and aesthetic stimuli of light, form and colour provided a source of inspiration for her artistic inventiveness.

Due to the omnipresent shortage of materials, she made mostly small-format works. More and more, these began to depict interiors such as hotel lobbies or cafés.

Material experiments: collage

Rösler’s playful approach to materials is particularly evident in her collages. They can be found even in her picture letters dated before 1945, for example in the Südlicher Hafen (ca. 1939). From the 1950s onwards, the artist turned to collage more frequently. Everyday finds became part of her visual worlds: “I have worked in many techniques, as I like to experiment. My favourite technique is collage. […] Using collage, I’m interested in making something precious out of the most banal things – usually scraps of paper that I find on the street.” And: “I’m particularly fond of iridescent tinfoil, which I like to use when imagining streets with illuminated adverts. ‘Picture gluing’ is one of my favourite techniques and fascinates me every time anew.”

Rösler was not especially interested in the materials’ significance or original context. Instead, she made use of the aesthetic effects created by texture and structure, colour and form. In Komposition (1950/51), for example, small pieces of newspaper are combined with drawn and watercolour areas to create a mosaic-like image. In Komposition mit rotem Mond 1952), oil paint, fabric and pearls are added – and in La Rue de la Gaîté (1953), various bits of tinfoil and paper are incorporated. These examples clearly show the extent to which Rösler’s surface-bound painting and drawing work and the collage technique were formally dependent on each other, even translated into one. However, the balance of the creative elements varied: the artist also produced sheets in which the glued pieces cover almost all the picture surface, so that the graphic additions recede into the background.

Abstract structure and movement: painting from the 1950s

From the mid-1950s, Louise Rösler began to work with larger formats, her compositions developing momentum and dynamism. Reference to the object receded further into the background, while the rhythmic arrangement of the picture surface into segments of colour and form grew more important. More and more, the artist was combining the individual pictorial elements into more expansive, cohesive forms.

She explained her working method in 1950: “There are no preliminary studies for my paintings! I don’t produce either sketches or watercolours beforehand. That has always been my way. […] It’s only in my mind that my pictures occupy me, often for a long time, before I paint them. – Then I scribble with a pencil on my canvas or board. – Later, I start to paint, but only when I see the exact colours and forms in front of me – I never experiment. […] – I have 2 different kinds of paintings, the ones I note down in 2-3 hours, like a letter; the others that need to grow gradually, often taking me weeks.”

Towards the end of the 1950s, Rösler moved away again from the expansive, two-dimensional compo-sitions in her paintings, lending the individual picture sections an additional sense of disquiet and dynamism with clearly visible linear structures.

“A new spatial dimension”: the painting of the 1960s and 1970s

Louise Rösler’s preference for curving and arching forms continued in her paintings of the 1960s and 1970s. Even before this, from the mid-1950s onwards, the artist had moved on to larger formats and more sweeping compositions. The element of movement became even more important from the 1960s onwards: At the beginning of this decade, her paintings were characterized by small-scale, vibrant, shimmering dynamics. Later, Rösler again grouped the pictorial elements together in larger, more cohesive sections, sometimes adding found objects.

Referring to the painting Straße mit Unterführung (1972), she stated: “I am currently using round boards to collage my painting ground. By incorporating these boards into my painting, along with the resulting sections and overlaps, I am arriving at a new spatial dimension that is emphasized even more by the flat relief.”

She also included a wide variety of materials in other works, some of which protrude distinctly from the picture surface. In the case of the painting Überdachte Straße (1978), for example, this is a round piece of sheet metal in the centre of the work. Other scraps of paper, sheet metal, felt and plastic elements are incorporated into the composition, turning the flat canvas surface into a relief: The elements used emphasize the materiality of the image as a whole.

Creating visibility

Louise Rösler’s extensive estate is an essential foundation for academic study of her life and work. It is a stroke of luck that it has been saved despite the many blows of fate and often precarious living conditions she faced – albeit with some parts missing due to the war. Over 1,000 works as well as letters, documents, photographs and catalogues have been preserved and are exhibited by her daughter Anka Kröhnke at the Atelierhaus Rösler-Kröhnke Museum in Kühlungsborn.

Intense research as well as detailed inspection and evaluation of the remaining estate material in the run-up to the exhibition has made it possible to clarify details of the artist’s biography. This includes analysis of her exhibitions, contacts, and membership in artists’ groups as well as insight into her evaluation in the context of contemporary art criticism. Ultimately, art-historical research is founded on such study and source work, although questions will always remain unanswered.

With this exhibition, the MGGU is contributing in another important way to making a wider public aware of artists outside the art-historical canon. The catalogue accompanying the exhibition aims to anchor Rösler and her work in public perception beyond the duration of the exhibition.

Documentation and reception

Louise Rösler’s biography, her artistic work and its reception were shaped by historical events and embedded in the social trends and upheavals of her time. Nevertheless, it is impressive to note the stead-fastness and determination with which the artist pursued, independently and unpretentiously, the continuation and development of her art – even in face of external obstacles.

Today, Rösler’s multifaceted œuvre is unknown to a broad public. Her career, which had begun full of hope before 1933, came to a standstill afterwards. Like other artists of her generation who remained in Germany and did not adapt resolutely to the political will and art understanding of the National Socialist dictatorship, opportunities for exhibitions, sales, publications, etc. were blocked almost entirely. This was compounded by serious personal blows and the loss of most of her previous work in bombing.

During the immediate post-war period, however, Rösler endeavoured to find fresh opportunities to exhibit and earn money. But she was only able to gain a foothold in the re-emerging art and cultural life of post-war West Germany occasionally. In addition to the generally difficult post-war situation, personal circumstances interfered with her public presence as an artist. Being the single mother of a young daughter, evacuated to a small town, meant that she lacked time, money and contacts.

However, the commitment of individual advocates, including the Düsseldorf art collector Hans Lühdorf, enabled Rösler to present her works repeatedly, finding recognition in solo and group exhibitions.

Freedom on paper

Louise Rösler’s rich œuvre includes not only paintings and collages, but also many watercolours, gouache works, coloured pencil and felt-tip pen drawings, and pastels. These developed an increasing significance in Rösler’s work as from the post-war years. Here, too, the artist always demonstrated great openness to a wide range of artistic techniques. Brimming with enthusiasm for experimentation and creativity, she utilized or combined various materials and drawing media depending on her artistic intentions – and even explored new technical possibilities.

The resulting works vary in complexity and dimensions, revealing the artist’s skill with both small and large formats. All are vivid and immediate, but also demonstrate the artist’s evident confidence regarding the visual effects appropriate to her applied materials and technique. Despite an apparent spontaneity and randomness, the artist’s concrete desire to shape and create was always the overriding premise in her compelling sensual exploration.

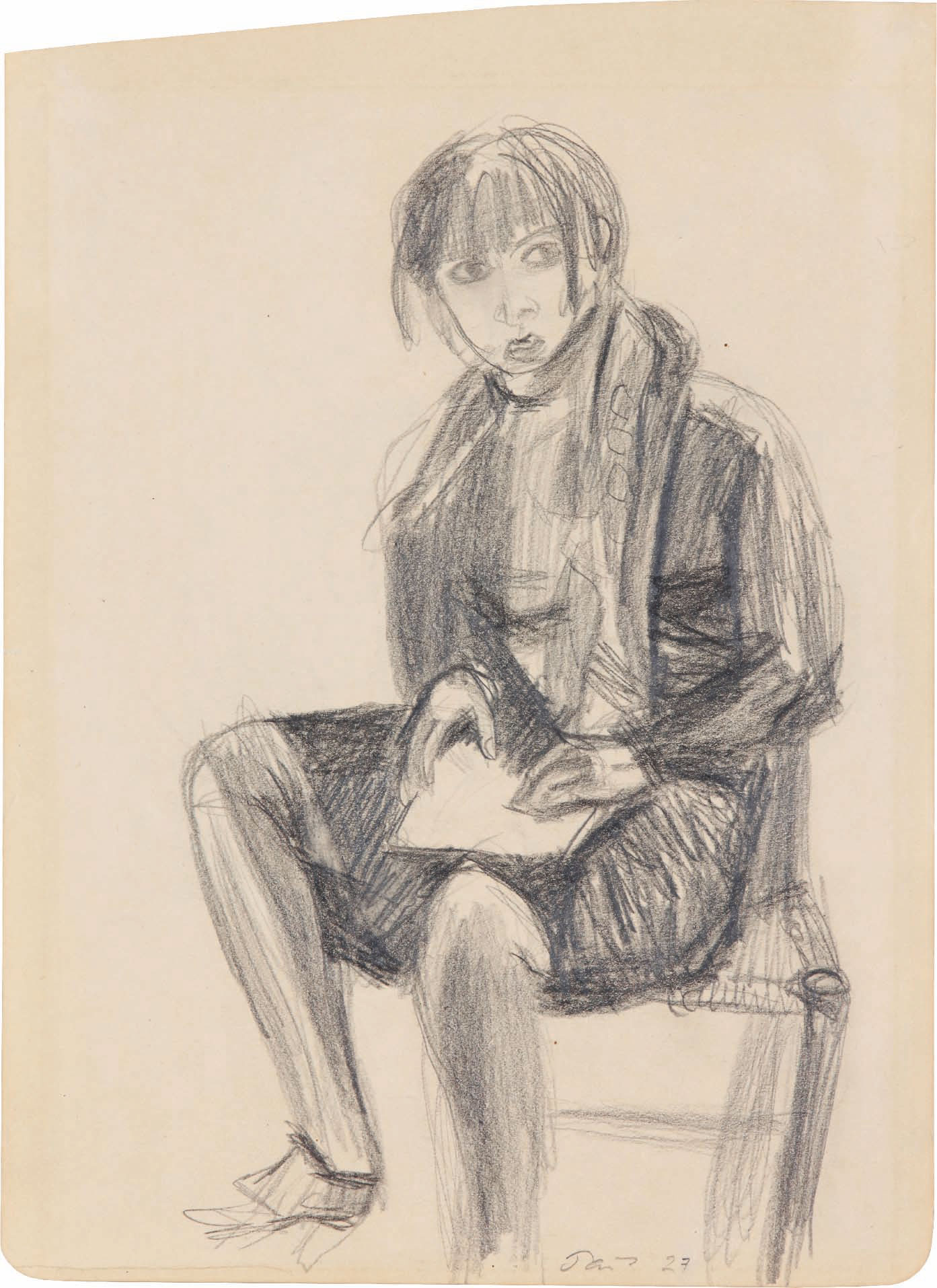

Black & white: drawing and printed graphic art

Colour plays a vital part in Louise Rösler’s work. Throughout her life, the artist drew inspiration from her own sensory experience of the seasons, weather, and materials to create intense compositions whose colours seem to radiate from within. Nevertheless, there are some works in her œuvre in which she dispensed with this creative potential: although black and white drawings and prints are the exception in Rösler’s œuvre, they testify to a joy in experimentation similar to that shown in her colour works. Rösler herself wrote in a letter dated 1966: “Black and white again, because I am fascinated by the range between black and white through shades of grey!”

The artist also tried her hand at printmaking and experimented with various techniques, particularly in the 1960s and 1970s: drypoint etching, zinc lithography, as well as wholly experimental prints such as Straße mit Unterführung (1967). Here, Rösler worked on a plastic plate with a soldering iron and a needle, producing a print from it. The imprint of the soldered, strongly heated plastic is noticeable on her print onto paper.

Colour as material: pastels

Rösler’s multifaceted post-war œuvre also includes pastels. This technique particularly emphasizes the haptic qualities of the material, which probably explains its appeal to the artist. In pastel technique, the colours – either as pure pigment or mixed with binding agents in the form of chalks or pencils – are applied directly to the picture support. They can be mixed and smudged together easily. However, the powdery consistency of the colours makes the finished works extremely sensitive. In addition, the painting surface must be rough so that the pigments will adhere to it. Rösler experimented with a wide range of carrying papers, the respective structure and colouring of which contribute decisively to the final pictorial effect.

The earliest known pastel, Straße in Königstein (1948), is on ribbed paper and reveals obvious formal parallels to the graphic-painterly work of those years. The pastels on a velvety paper produced in the mid-1950s are particularly powerful and sensual. The lush effect of the loose colour pigments is enhanced by the matt, open paper surface. In the works In den Anlagen (Dennewitzplatz) (1961) and Weite Stadtlandschaft (1962), the artist combined the oily pastels with the technique of frottage, creating an artistic effect by rubbing off a structured surface. The pastels, executed on Japanese paper, show the structure of the wooden board lying underneath during the working process. Afterwards, the artist backed the sheets with brown cardboard to recreate the chromatic impression present during the painting process.

From flat surface into space: assemblages and sculptures

While Rösler preferred to work with found objects made of paper or tinfoil in the 1950s, she subsequently expanded her range of materials, incorporating moulded wooden, plastic or metal elements into her works. The artist created painted collages, primarily made of wood, also using round or oval shapes as a picture format. In addition, she produced works whereby she inserted a wide variety of materials into the object’s surface and left them more or less as they were. The visual appeal of the respective material used in this way complements the haptic qualities of the collaged elements.

In her collages and assemblages, Rösler always started out from the material she had found. She began by placing individual elements onto the picture support and then layering them to create the overall image. The diversity of the material and its aesthetic appeal took centre stage. This approach is exemplified in Tivolivariation (1967): whether corrugated cardboard, punched card, or blistered pill-packaging – everything combines to form a whole on the relief-like picture surface. At the same time, the historical context is visible because of the material used. Like many of Rösler’s other collages, this work conveys cultural history: not as a superficial artistic intention but as an inherent characteristic of the materials themselves.

The artist’s playful approach to found materials is also evident in the four sculptural works she made using shoe-trees in the early 1970s. Their titles refer humorously to the respective source of inspiration – Im Dürerjahr, Hommage à Naum Gabo, Antipoden and Die Nonne. Here, the artist has transposed her artistic inventions from the wall into the room. The starting point for these small sculptures is the found material itself.

The flâneur: late work as a painter

Whether abstract or object-related: Louise Rösler remained true to the topic of the big city into her late work. Throughout her artistic career, the urban offered her vital inspiration. It appears again and again in her paintings, collages, and drawings.

In her late work from the 1980s, the metropolis became more figurative once again, and therefore more tangible as well as monumental in format. The architecture of Görlitzer Bahnhof (1987) reaches towards us, massive and simultaneously dynamic. Crowds of people in motion are recognizable passing in the foreground, while the silhouettes of Kreuzberg housing in the background complete the cityscape.

Bahnhof Zoo (1980) displays a similar composition, and, with the station building, evokes similar architecture to Görlitz station. Even more apparent here is Rösler’s interest in the rounded and curving lines that lend pace to the scene and visualize urban life and experience with its full dynamism.

Until the end of her life, Rösler retained her own personal view of the city – especially of her home town, Berlin.

Visit

Opening Hours

| Tue, Wed, Fri, Sat, Sun | 10 am – 6 pm |

| Thu | 10 am – 8 pm |

on public holidays open from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m.

Admission

| Adults | 7 € |

| Reduced | 5 € |

| Holders of the Frankfurt-Card | 2,50 € |

| Holders of the Kulturpass | 1 € |

Contact

Museum Giersch der Goethe-Universität

Schaumainkai 83 (Museumsufer)

60596 Frankfurt am Main

Tel. 069 / 1382101-0

Fax 069 / 1382101-11

Mail info@mggu.de

Reduced and free admission

Reduced admission:

- Students (except Goethe University Frankfurt)

- Unemployed persons

- Severely disabled persons

- Group (of 10 or more people) per person

Free admission:

- People aged 18 and below (children aged under 14 only when accompanied by an adult)

- School classes

- Accompanying person for the severely disabled

- Students of the Goethe University Frankfurt with valid semester ID

- Art history students with valid semester ID

- Students of the HfMDK, Frankfurt am Main

- Holders of the Museumsufer Card / Museumsufer Ticket

- Holders of the Goethe Card (employee at the Goethe University Frankfurt) or holders of a validated U3L card

- Holders of the Goethe University alumni card

- Employees and students at the Frankfurt University of Applied Sciences

- Holders of an ICOM card

- Members of the Association Verband Deutscher Kunsthistoriker e.V.

- Members of the Federal Association Bundesverband freiberuflicher Ethnolog_innen e.V. (bfe)

- Employees of other museums with ID / certificate

- Press with press card

- Refugees from Ukraine, Syria and elsewhere

- Holders of the volunteer card

How to get here

by public transport

Tram 12 / 15 / 16 / 17 21

to Stresemannallee/Gartenstraße

Underground U1 / U2 / U3 / U8

to Schweizer Platz

15 minutes‘ walk from Frankfurt main station

by car

Car Parks

Walter-Kolb-Straße 16 (Alt-Sachsenhausen)

Willy-Brandt-Platz 5 (Schauspiel Frankfurt)

Untermainanlage 1 (Untermainanlage)

Barrier-free

For visitors with limited mobility and visitors with prams or pushchairs, the Museum Giersch of Goethe University is accessible by way of a lift. The lift is located on the east side of the building, behind the entrance stairs. We recommend for an accompanying person to contact our colleagues at the information desk in the museum for support. Wheelchair-accessible restrooms are located in the basement.

Folding stools can be borrowed for your visit on the first floor next to the entrance of the exhibition.

Museum

The Museum Giersch of Goethe University is an exhibition center for art, culture, and science. Since its founding by the Giersch Foundation in the year 2000, its focus has been geographical on the Rhine-Main region. Within this parameter, the museum devotes itself to the discovery, study, and communication of hitherto little-noticed artistic oeuvres and cultural phenomena of all epochs to the very present.

The museum has belonged to the Goethe University since 2015. This affiliation has broadened its exhibition spectrum to include themes from the research and teaching pursued at the university. The museum moreover frequently cooperates with the institutes, scientists, teachers, and students as well as the collections of the Goethe University. As ‘the university’s window on the city’ it promotes the communication between art, science, and the public and, with its wide range of educational and communication activities, contributes to societal discourse as a whole.

Building

The Museum Giersch of Goethe University is located in a villa on the Sachsenhausen bank of the River Main. The three-story Neoclassicist-style mansion was built for the Holzmanns, a construction contractors’ family of Frankfurt, in 1910.

The Giersch Foundation purchased the building from the City of Frankfurt in 1998. In keeping with the rigorous requirements for the preservation of historical monuments, the new owners immediately set about having it altered to serve as an exhibition gallery, complete with barrier-free access and state-of-the-art air-quality-control and security standards. The gallery opened to the public in 2000. With their original wood panelling, the rooms on the ground floor still convey an impression of the villa’s onetime domestic character. The exhibition rooms on the upper floors, for their part, are modern in look and feel. Thanks to their compartmentalized structure, they are well-suited to accommodate the needs of the changing exhibitions.

In the villa’s garden, the Giersch Foundation had a duck fountain built with original bronze figures by the sculpture August Gaul. The design is modelled on that of a fountain in Berlin of the year 1911.

In 2020/21, the Giersch Foundation and the Goethe University had the building’s air-quality-control, security, and fire-prevention systems thoroughly overhauled. The lighting in the exhibition rooms was moreover converted for the use of energy-efficient LED spotlights.

History

On 24 September 2000, the non-profit Giersch Foundation opened its new exhibition center, the Haus Giersch—Museum Regionaler Kunst. The initiative for the founding had come from Honorary Senator Prof. Carlo Giersch and his wife, Honorary Senator Karin Giersch. Their aim was to create a public exhibition gallery for the presentation of hitherto unresearched facets of the history of Rhine-Main art and culture that would be of interest beyond regional boundaries.

The programme initially concentrated on surveys and monographic exhibitions of nineteenth- and early twentieth-century painting of the Rhine-Main region. Over the years, the spectrum of topics gradually broadened to encompass other artistic mediums such as sculpture, photography, graphic arts, and book art. The temporal focus widened as well and meanwhile extends from the Early Modern period to the present. A special focus of the gallery’s activities was and is the presentation and communication of its research results in accompanying catalogues and museum education work. The Museum Giersch has thus carved out a firm place for itself within the city’s wide array of museums.

In 2014, the year marking the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Goethe University, the Giersch Foundation turned the exhibition center’s operation over to the university. Since 2015, it has been known as the Museum Giersch of Goethe University. As before, it is devoted to the art and culture of the Rhine-Main region and now also presents exhibitions related specifically to the past and present of the Goethe University and its collections. It moreover serves as an event venue and place of encounter for the university community.