25. Oktober 2024 bis 16. Februar 2025

OUR HOUSE

Künstlerische Positionen zum Wohnen

OUR HOUSE: Unser Haus, das ist das Gebäude des Museum Giersch der Goethe-Universität, eine Villa mit Geschichte. 1910 als Wohnhaus gebaut, später Sitz der spanischen Handelskammer, ist es seit dem Jahr 2000 ein Museum. Die familiäre, private Atmosphäre der ehemaligen Wohnräume fasziniert die Besucher*innen seit jeher. Nun steht dieser Wohncharakter des Hauses selbst im Fokus des Ausstellungsprojektes OUR HOUSE. Künstlerische Positionen zum Wohnen.

Nichts ist zugleich so privat wie öffentlich wie das Wohnen. Die eigenen vier Wände sind ein menschliches Grundbedürfnis. Angesichts steigender Mietpreise und knappem Wohnraum wird die Frage nach dem gerechten, nachhaltigen und guten Wohnen heute wieder mit großer Dringlichkeit politisch und gesellschaftlich debattiert. Wie wohnen wir? Wie prekär gestalten sich manche Wohnsituationen, und wie kann Wohnen zukünftig gedacht werden? Diese Fragen werfen die teilnehmenden Künstler*innen auf und nehmen dabei zugleich auch Bezug auf die Raumsituation des Museumsgebäudes.

Zu sehen sind Werke zeitgenössischer Künstler*innen wie Matthias Weischer und Susanne Kutter, aber auch historische Positionen wie der Wiener Fotograf Robert Haas oder die Frankfurter Fotografin Inge Werth. Sie beschäftigen sich mit den unterschiedlichsten Facetten des Wohnens vom Interieur als ästhetische Bühne über die prekäre Wohnsituation geflüchteter Menschen bis hin zum klaustrophobischen Innenraum der Corona-Lockdowns. Die Berliner Künstlerin Jana Sophia Nolle entwickelt für die Ausstellung eine neue Arbeit, die sich mit der wachsenden sozialen Ungleichheit auseinandersetzt, welche sich in unterschiedlichen Wohnrealitäten manifestiert. Auch der Künstler Jakob Sturm wird sich in einer neu entstehenden installativen Arbeit mit der Thematik des Wohnens und des Wohnraums in Frankfurt beschäftigen. Ein besonderer Part kommt der Schweizer Künstlerin Zilla Leutenegger zu, die sich durch umfassende künstlerische Interventionen kritisch mit der Museumsvilla auseinandersetzt.

Das Projekt ist Teil der Kooperation INTERIOR, der neben dem MGGU noch fünf weitere Kulturinstitutionen der Region angehören: Die Kunst- und Kulturstiftung Opelvillen Rüsselsheim, das Museum Sinclair-Haus in Bad Homburg, das Kunstforum der TU Darmstadt sowie das Kunsthaus Wiesbaden und der Nassauische Kunstverein Wiesbaden.

Die Storyguides zur Geschichte der Häuser aller INTERIOR-Kooperationspartner können abgerufen werden unter: https://interior-rheinmain.de/de/

Künstler*innen:

Francisca Gómez

Robert Haas

Karolina Horner

Susanne Kutter

Zilla Leutenegger

Morgenstern & Wildegans

Jana Sophia Nolle

Elizabeth Ravn

Jakob Sturm

Matthias Weischer

Inge Werth

Sie sehen gerade einen Platzhalterinhalt von YouTube. Um auf den eigentlichen Inhalt zuzugreifen, klicken Sie auf die Schaltfläche unten. Bitte beachten Sie, dass dabei Daten an Drittanbieter weitergegeben werden.

Mehr InformationenExhibition Tour

Introduction

Welcome to OUR HOUSE! The Museum Giersch der Goethe-Universität is housed in a historical villa. Built as a private home in 1910, it was later occupied by the Spanish Chamber of Commerce and became a museum in the year 2000. The building’s original purpose, which can still be felt in the homely atmosphere of its formerly domestic interiors, make it an ideal venue for this exhibition. After all, nothing is as private and public, as personal and political, as habitation. How do we live? How much living space can we afford and how do we fashion it? These are the questions the participating artists explore in their works. The exhibition itself is conceived as a “shared house” whose rooms are each “occupied” by a different artist and his or her works.

Zilla Leutenegger’s site-specific installations on the ground floor, in the cellar and in the stairwell show her engaging with the villa’s past as a private dwelling. The first and second floors of the “shared house” comprise nine separate rooms, each with a different take on the subject of habitation and housing. While Matthias Weischer treats living space as an aesthetic platform, Susanne Kutter brutally deconstructs it. The Frankfurt-based photographer Inge Werth, for her part, presents a visual record, compiled over several decades, of the bedrooms slept in by people of all classes. The Austrian photographer Robert Haas was commissioned by Jews who had fled Vienna in 1938 to memorialise the homes they had had to abandon. Still other works reflect on some of today’s most pressing problems: Francisca Gómez, for example, addresses the precarious living situation of refugees, while Karolina Horner and Elizabeth Ravn grapple with the challenges posed by the COVID lockdowns. Meanwhile, Jakob Sturm and Jana Sophia Nolle chose the dire housing situation in Frankfurt am Main as their subject. The work they developed specially for the exhibition is a critical engagement with the city’s growing social inequality. The exhibition design is the work of Marcus Morgenstern, who endowed the temporary “shared house” with both a ground-floor kitchen and a first-floor living room in which guests are welcome to take a break and feel at home.

Artists

Zilla Leutenegger

Zilla Leutenegger (b. 1968) works with installations at the interface of drawing, sculpture and video. Her works turn on the relationship between humans and space. The six site-specific installations she created for OUR HOUSE include a completely new production made specifically for what used to be the master’s study.

What are your exhibited works all about?

They are about who lives here. Are we really alone when we come to visit?

What interests you about housing?

What does it mean for a residential building to become a museum?

How might we live in future?

The kind of home in which we each feel comfortable is bound to be highly individual. But one aspect that is undoubtedly true of all cultures is the need to feel safe.

Jakob Sturm

Jakob Sturm (b. 1966) is an artist, author and curator with a particular interest in the production of spaces.

What is your exhibited work all about?

It is about how we live and how we want to live. This question is of fundamental concern to us all and to society as a whole – perhaps more than almost anything else in art.

What interests you about housing?

That it is at once both private and political. One constant of my work is the creation of “places of possible habitation” both in reality and in art, since to me, there is not much difference between the two. As I see it, the question of how we live begins with how we relate to each other and to things, and how we share space.

How might we live in future?

Hopefully in a way that our interactions with space and things are constantly opening up new possibilities and becoming less and less constricting, both politically and socially; and in a way that our sharing of space and our housing preferences no longer depend on economic parameters.

Inge Werth

Born in Stettin in 1931, Inge Werth launched her career as a photographer in Frankfurt in 1963. She ranks alongside Barbara Klemm, Abisag Tüllmann and Erika Sulzer-Kleinemeier as one of the key eye-witness photographers of the revolts of 1968. She also observed and photographed the mounting protests against property speculation and high rents of the early 1970s as well as photographing the first occupied houses in Frankfurt’s West End. Werth’s focus as a photographer was always on the needs and living conditions of the people she photographed and the quality of their abodes.

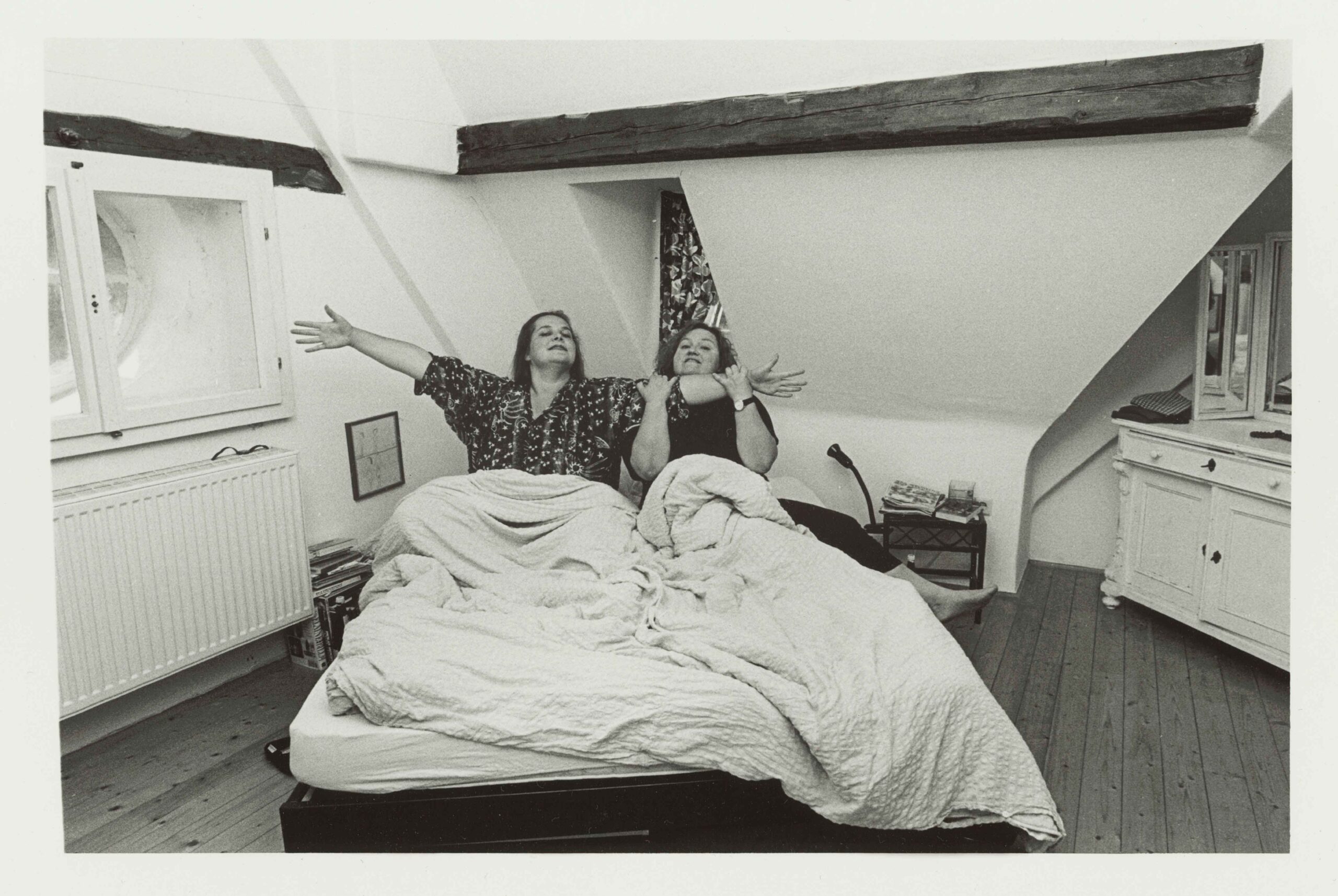

Werth began her Im Bett series in the 1970s and worked on it for several decades. The series came about almost by chance. She had been working on a project about rural life that had also entailed capturing people in their most personal space, i.e. in their bedrooms. The subject so captivated her that she began visiting families, couples, men, women and people young and old from all social classes and all walks of life and using her camera to record the variety, the peculiarities and the personal touches that characterise every home, the purest expression of which she invariably found in that most private of all rooms, the bedroom. What interested her was always the inhabitants themselves and the questions: How do these people live? What do they surround themselves with? What are the memories they cherish most?

This room shows a selection of images from the Im Bett series as well as three photographs that Inge Werth has taken within the past few years in the senior citizens’ home in which she now lives.

Matthias Weischer

Matthias Weischer (b. 1973) is a painter and draughtsman. He is interested in living space as an interior and as a performance space that he can constantly restage.

What are your exhibited works all about?

This room is both motif and studio rolled into one; it is a model that I am actively working on and that I am constantly changing. Here, I observe, arrange, draw and paint. The room is separated from infinite space, yet for all its limitations offers unlimited possibilities. This is the first time I have gone public with this practice of working with a playable space outside my own studio.

What interests you about housing?

To inhabit a space means to adapt it and shape it. It follows that where a person lives is bound to be an expression of an individual, subject to external constraints and that person’s own possibilities. Housing is a fundamental need and engenders security. Having said that, any space can accommodate an arrangement of interest to me, whether or not it is secure. The factors that matter are often quite basic: What is the fall of light? How are the objects spaced and how do they relate to each other? Space is a universal language that I am constantly parsing anew… as is anyone who inhabits a space.

How might we live in future?

Our needs will not change, I believe, though external pressures and the need to adapt to changing conditions will inevitably result in differents forms of habitation. Climate change, digitalization and scarcity of resources will undoubtedly play a role. But housing is a cultural phenomenon that is evolving all the time and that changes only gradually. So there will still be chairs, cupboards, beds and pictures on the walls – that much seems certain.

Susanne Kutter

Susanne Kutter (b. 1971) is a multimedia artist who is interested in the precarious relationship between nature and culture. The loss of certainties now threatening us also informs her engagement with living space.

What is your exhibited work all about?

It is about the destruction of space, the loss of security and continuity and perhaps even the dissolution of the conventional order. But it is also about the round and the angular and how illusions are generated.

What interests you about housing?

Many creatures build themselves a nest, a lair or an underground burrow. Shaping space to make it habitable is not a behaviour exclusive to Homo sapiens. But there are additional factors that play a crucial role in the creation of human dwellings – factors such as power, status, social exclusion.

How might we live in future?

Who will have how much space at their disposal? The distribution of living space reflects the perverse, capitalistic power structures underpinning our society. The right to living space is not a human right. So my answer to the question of how we might live in future is that having sufficient living space at our disposal should be declared a universal human right.

Jana Sophia Nolle

Jana Sophia Nolle (b. 1986) works at the interface of conceptual photography, installations and artistic research. Her work Blue Blanket was created specially for the OUR HOUSE exhibition. The title is a reference to the blue blankets used by homeless people that are a frequent sight in Frankfurt.

What is your exhibited work all about?

Blue Blanket shows a fictional living room of a well-to-do Frankfurt resident. It is a synthesis of photos of Frankfurt living rooms taken for research purposes. Inside this living room is a reconstruction of a homeless shelter of Frankfurt sleeping places. The work addresses the ever widening gap between rich and poor in Frankfurt, and taking housing as an example, examines the far-reaching socio-political changes currently taking place there, including the dynamics of gentrification and marginalization.

What interests you about housing?

At a time of growing social inequality, I have chosen to address people’s existential need for shelter and safety and the relevance of people’s actual living conditions to the wider issue of social justice. In terms of both form and content, my works take place in public and in private. They open up alternative spaces such as footpaths and living rooms as platforms on which the definition and influential scope of the public and private spheres can be negotiated.

How might we live in future?

Growing cities, increasingly limited living space and climate change all call for a complex rethink to which city planners, architects, designers, policymakers and others should take an interdisciplinary approach. Housing, and construction generally, should be sustainable, energy-efficient and carbon-neutral. The interiors of buildings could be designed so as to be multi-functional, making it easier for them to be repurposed. Autonomous communal housing could become a more readily available option and private ownership scaled back. At the political level, it is important to create more affordable housing and that our living spaces focus on people as well as on nature.

Elizabeth Ravn

Elizabeth Ravn (b. 1994) creates paintings in which she devotes herself to the humdrum, the private, the seemingly incidental. Her works capture fleeting moments in much the same way as snapshots.

What are your exhibited works all about?

The works are from a series I produced while confined to my apartment during the first COVID lockdown in 2020. Started spontaneously in an effort to preoccupy myself, the series has become a record of my place in uncertain times.

What interests you about housing?

Housing is a recurring consideration in my work, as a context for the everyday and as a representation of precarity and transformation. Dwelling in cities, I encounter inspiring heterogeneity in housing, while also being constantly confronted by the exploitation of housing for profit.

How might we live in future?

After recent years of pandemic-induced home time, we could live with a more sincere appreciation of housing. We could make housing more accessible to all, rather than speculating, destroying, or displacing people from their homes.

Karolina Horner

The photographer Karolina Horner (b. 1980) lives and works in Vienna. In 2020 she recorded the lives of various families there during the COVID lockdown.

What are your exhibited works all about?

The first COVID lockdown imposed in March/April 2020 brought ordinary life to a standstill literally overnight. Suddenly, everyone’s lives were confined to their own four walls. For me this meant that I was no longer allowed to follow the lives of the families I had been following as a photographer. To cope better with the uncertain and unsettling state of being locked up at home, and to continue taking photographs, I decided to use the computer to record the lives of families now forced to do everything within their own four walls. We met on Zoom, when I would ask the family members to congregate in one room and there do something representative of their everyday lives during lockdown. I then photographed them doing it without having to leave my own four walls.

What interests you about housing?

I’m interested in how families organise their home life, the rituals they develop and how these rituals changed as a result of their living on top of each other during the pandemic, or rather the lockdown.

How might we live in future?

I would like to see children and families living in a way that makes them feel safe and secure. I would like children to experience the home as a kind of nest in which they can grow up in safety and experience magic in their everyday lives as they slowly but surely advance towards adulthood. Sadly, this is still beyond the reach of far too many children and families.

Robert Haas

Robert Haas (Vienna 1898 – New York 1997) was an Austrian-American photographer. Having won recognition as a typographer in the 1920s, he served an apprenticeship with the Viennese photographer Trude Fleischmann before embarking on a career in photojournalism. The 1930s saw him produce numerous photo-essays on everyday life and social issues. Haas was Jewish and escaped Austria only by the skin of his teeth in 1938. He fled first to England and then to the USA, where he launched his second career as a graphic designer and printer, though he never gave up photography.

Robert Haas’s photographic estate was made over to the Wien Museum in 2015. There it was found to contain numerous interior views of the homes of Jewish residents of Vienna who had been forced to flee Austria following its annexation by Nazi Germany in 1937–38.

The reproductions of the photographs exhibited in this room show the abandoned homes of five Jewish families and individuals, who commissioned Haas to produce a visual record of their former homes. Three of the commissions were executed on the same day and are dated June 1938, when Haas himself was preparing to flee. He left Austria for good in September of that year.

Further reading:

Frauke Kreutler & Gerhard Milchram, “Zum Andenken verewigt. Wiener Wohnungen 1938,” in Wien Museum Magazin, 2019.

https://magazin.wienmuseum.at/wiener-wohnungen-1938

The situation for the Jewish photographer Robert Haas became even more perilous when Nazi troops marched into Austria in March 1938 and annexed it to Nazi Germany: “As you know,” he wrote to a friend in the USA in April 1938, “I will not be able to remain here and I’m already pulling all the strings I can to get out.” The persecution, deportation and murder of the Jews of Vienna between 1938 and 1942 led to 70,000 homes becoming “vacant.” Most of these were allocated to loyal Nazis. Some Jews who were already living in exile commissioned Haas to photograph their abandoned homes for them, presumably as a memento, but perhaps also to have a record of the property they had lost.

Louise Stern’s letter to Haas of 28 May 1938, for example, contains detailed instructions on what to photograph: “Dear Mr. Haas, In my amateurish way, I’ve drawn up a list of the things I would like to have memorialised.” Stern goes on to describe the rooms and furnishings that she wants to have photographed: “Small hall (downstairs) display cabinet with Tyrolean chairs, stove (illuminated, though it also looks good from the stairs). The suite of red chairs (if the lamp is in the way, please move it) with the plates on the wall and the banisters (a favourite view of mine.)” Haas photographed the Sterns’ apartment according to his client’s instructions on 8th June. He had to work clandestinely in order not to attract the notice of the neighbours, who might otherwise have alerted the Gestapo. Whether Louise Stern ever received the photographs is not known. She took her own life in Prague in 1939. Her husband Gustav survived the Shoah.

Francisca Gómez

The photographs of Francisca Gómez (b. 1981) record an experiment conducted on herself. In 2015, Gómez reconstructed the kind of emergency shelter provided for refugees arriving in Germany and, after furnishing it with the bare necessities, lived there herself before letting a friend of hers, who had fled from Syria with just a few personal possessions, “move in” for a few days.

What is your exhibited work all about?

Can any architectural structure be made habitable – and should it? Which things do we really need or should we be allowed to keep when space is limited? The average refugee arriving in Germany at the end of 2015 was allotted 3.5 m2 living space.

What interests you about housing?

I understand dwellings as social corpuses, as a kind of second skin that also functions as a dividing line between social status and individual action. Housing is an existential need, which is why it speaks volumes about the health of a society.

How might we live in future?

Housing is one of the most pressing problems of the present. To be able to make meaningful changes to it, we first have to get to grips with the deep-seated question of private property and wealth distribution.

Housing in Frankfurt

Housing in Frankfurt?

What is the housing situation in Frankfurt am Main? The boards here in the hall address the positive and problematic aspects of housing and illustrate these with telling facts and figures. After all, with the construction of new housing almost at a standstill and rents steadily rising, Frankfurt’s housing market is becoming increasingly difficult to navigate, especially for people on low incomes and on the fringes of society.

The aspects and problems selected are intended to shine a spotlight on the subject of habitation generally, and are by no means exhaustive. Some relate directly to the themes chosen by the artists whose works are exhibited in the various rooms. Each board combines interesting statistics with information on the larger context. Anyone wishing to know more about the subjects addressed can use the QR codes to access City of Frankfurt websites, private and public initiatives and press coverage of the topic. Located on the right-hand side of the hall of our “shared house” is a living room with bookshelves full of books on housing that you are welcome to peruse. Which aspects of the subject matter most to you? Use the living-room noticeboard to share your thoughts with us!

How do we live in Frankfurt am Main?

Frankfurt currently has 770,000 inhabitants living in approx. 81,000 residential buildings. Apartment buildings account for 50% and hence the largest share of this total. Single-family dwellings account for a further 36% and semi-detached houses and duplexes for approx. 13%. The average Frankfurt household consists of 1.8 persons. Each inhabitant has an average of 38.9 m2 living space at his or her disposal.

What does social housing provision mean?

Social housing provision means the provision of appropriate housing for all citizens. People who struggle with their monthly rental payments can receive government support in the form of a housing allowance called Wohngeld. A total of 4,325 Frankfurt households received Wohngeld in 2021. The average claim was € 255 per month.

People who need a new abode but cannot afford anything on the housing market may qualify for government-funded housing, also known as social housing. A 2015 survey by the Institut für Wohnen und Umwelt revealed that this is true of 49% of all households living in rented accommodation. Individuals with a gross annual income of less than € 27,100 and couples with two children with a gross annual income of less than € 66,500 may be eligible to apply. Frankfurt’s social housing stock has been dwindling for decades, however, so the waiting list is long.

Find out here if you are eligible for Wohngeld:

https://www.bmwsb.bund.de/Webs/BMWSB/DE/themen/stadt-wohnen/wohnraumfoerderung/wohngeld/wohngeldrechner-2023-artikel.html

Does having nowhere to live make you homeless?

Some 3,708 Frankfurt residents currently have nowhere to live and are accommodated in the city’s communal shelters.

Some 300 people in Frankfurt metropolitan area currently have no roof over their heads.

People who have nowhere to live, whether because they were evicted, because their home became uninhabitable or for other reasons, and who are living with friends or in one of the city’s shelters are by definition Wohnungslos, that is, without anywhere to live.

Homeless people, by contrast, are Obdachlos, meaning that they have no roof over their heads and live on the streets. The city caters to the homeless by providing emergency shelters like the one at Eschenheimer Tor and services like the Kältebus, a bus that distributes blankets, sleeping bags and hot tea.

Homeless women are especially at risk of violent attack. A Germany-wide survey by the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs revealed that 79% of respondents had experienced violence at first hand. Yet many still chose not to make use of emergency shelters for fear of being robbed or attacked. Of the homeless respondents, 41% explained that emergency shelters were “too dangerous” to be an option for them.

Further information for those without anywhere to live or interested in doing volunteer work among the homeless:

https://www.frankfurt-hilft.de/

Who does the city belong to?

The first residential property in Germany to be taken over by squatters was in Frankfurt. That was on 19 September 1970, and over the months and years that followed, squatters took possession of still more vacant properties. Their aim was to establish a participatory model of urban development and to prevent living space being converted into office space. Other forms of protest such as rent strikes – the withholding of rental payments – also gained traction as a way of resisting rent hikes and evictions. Although many squatters were forcibly evicted by the police, some were able to remain in the buildings they had taken over and still live there today. Evictions in which tenants are forced out are still taking place in Frankfurt even today, whether to enable extensive renovation work or for other reasons. Activists, moreover, are still occupying buildings in protest against such practices, and against plans to demolish buildings or leave them vacant.

The City of Frankfurt has a Tenant Protection Unit that can advise you on your rights as a tenant and help you in the event of conflicts with your lessor:

https://frankfurt.de/themen/planen-bauen-und-wohnen/wohnen/mietrechtliche-beratung/stabsstelle-mieterschutz

How do students live?

A room in a shared flat or house in Frankfurt costs € 670 per month on average. The equivalent figure for Germany as a whole is € 479 per month.

Recipients of BAföG (government-subsidised student loans) are to receive a housing allowance of € 380 per month for the winter semester 2024/25.

Of Germany’s students, 86.2% live in a city in which the BAföG housing allowance does not cover the cost of an average room in a shared flat or house. The discrepancy in Frankfurt is especially great. Only in Munich do students pay more for a room in shared accommodation. At the same time, Frankfurt lacks halls of residence and dorms. The Studierendenwerk Frankfurt currently manages 3,267 places in halls of residence, and has almost as many applicants on its waiting lists. An additional 266 rooms were made available for the summer semester 2024.

Students at institutions of higher education in the Rhein-Main region generally look for a room via www.wohnraum-gesucht.de. Private individuals interested in renting out rooms to students, whether for a few weeks or a few months, can do so here:

https://www.wohnraum-gesucht.de/hintergrund

How discriminatory is the housing market?

Average living space per person in Frankfurt:

34.9 square metres for non-migrants living together in one unit

24.3 square metres for migrants living together in one unit

Monthly rent burden in Frankfurt:

Non-migrant households spend a quarter of their household income on rent on average.

Migrant households spend a third of their household income on rent on average.

People with a migrant background are more likely than other tenants to be affected by housing market tensions, displacement and discrimination, and not just in Frankfurt. Studies show that people with a migrant background have less living space at their disposal and pay higher rents than the population at large.

The discrimination begins with the selection of potential tenants: In Frankfurt, applicants with a “foreign-sounding” name are 30% less likely to be invited to a viewing than are other potential tenants, according to a 2017 study by Der Spiegel and Bayerischer Rundfunk.

Other groups may also suffer discrimination – say on grounds of sex, sexuality or religion –although there are no statistics to prove this.

The detailed study by Der Spiegel and Bayerischer Rundfunk can be viewed here:

https://www.hanna-und-ismail.de

How do refugees live?

Frankfurt is currently providing shelter for 5,628 refugees.

They are housed in 77 emergency and temporary shelters and in 24 hotels.

Since 2015, Frankfurt’s Unit for Accommodation Management and Refugees has inspected 1,565 buildings and plots to ascertain their suitability as refugee housing.

There are people of over 180 different nationalities living in Frankfurt. This figure includes refugees, for whom the search for affordable housing tends to be especially difficult. Many therefore spend years living in crowded communal shelters. Some of these shelters were designed to be emergency shelters only. The berths provided in converted gyms and shipping containers, for example, are separated by no more than flimsy partitions and contain only rudimentary furnishings (bed, table, chair, locker). Temporary housing, by contrast, features lockable units offering greater privacy and the option of self-catering. This is true of many hostels and hotels.

If you would like to offer a refugee or refugees somewhere to live, you can contact the city’s Unit for Accommodation Management and Refugees here:

https://gefluechtete-frankfurt.de/

A House with a History

On entering the Museum Giersch der Goethe-Universität the visitor is immediately struck by the intimate, homely atmosphere of these formerly domestic interiors. So who actually lived here? And what times has the villa itself “lived through” in the course of its 100-year history? These are questions that you can explore in more depth here. The three screens are an invitation to discover more about the villa in a digital Story Guide. Each screen is dedicated to a different chapter in the villa’s history. Chapter 1 sheds light on the period from its construction in 1910 to the late 1930s, when it was the private residence of the Holzmanns, a family of building contractors. Chapter 2 focuses on the period 1940 to 1997, when the Spanish Chamber of Commerce used it as business premises. Chapter 3 is all about the present, that is, the period since 2000, when the villa was chosen to house the Museum Giersch der Goethe-Universität.

The Story Guide was developed as part of a project called INTERIOR that comprises six cultural institutions altogether. The other five are the Kunst- und Kulturstiftung Opelvillen Rüsselsheim, the Museum Sinclair-Haus in Bad Homburg, the Kunstforum der Technischen Universität Darmstadt, the Kunsthaus Wiesbaden and the Nassauische Kunstverein Wiesbaden. What all these institutions have in common is that they occupy buildings that were originally built for a completely different purpose.

You can find out more about our partner institutions here:

https://interior-rheinmain.de/de/

The Story Guide to the Museum Giersch can be purchased as a brochure at the ticket desk, it includes an English text version.

Kitchen and Living Room

Living room/Wohnzimmer

Please feel at home! Take a seat, browse the bookshelves, or simply relax and savour the view of the River Main and the Frankfurt skyline. You can also use the noticeboard to share your own thoughts on housing with us. Pens and Post-Its are provided

Pinnwand

Communal living, rent hikes, housing shortages: What concerns you most about the current housing situation?

Kitchen/Küche

Every shared house has one and it’s invariably where all the action is… Yes, you guessed right: the kitchen! OUR HOUSE is the first exhibition at the Museum Giersch to open the kitchen to visitors. So take a seat and help yourself to a drink from the fridge (soft drinks, mineral water) or make yourself a coffee. There’s a price list on the counter and you are kindly requested to pay for your drink at the ticket desk.

Contextualization: Fritz Klimsch

Fritz Klimsch (1870–1960)

Jugend [Youth]

1940/41

This bronze sculpture is an idealised representation of Margrit Schlömer, who was nineteen at the time. To the artist, she was the very epitome of beauty and youth. In his depiction of her, he leaned heavily on the models of Graeco-Roman Antiquity. Klimsch was among those to profit from the Nazi regime, despite never actually joining the Nazi Party. On the direct orders of Adolf Hitler and Joseph Goebbels, his name was added to the “Sonderliste A,” also known as the “Gottbegnadeten-Liste” [List of God´s blessed] which numbered only twelve visual artists. As “national capital of overriding importance,” they were to be allowed to work unimpeded during the Second World War. Jugend was the only nude sculpture by Klimsch intended for Adolf Hitler’s “Führer Museum” in Linz, which was to be the “greatest art gallery in the world.” In 1942, a cast of the sculpture was shown at the “Große Deutsche Kunstausstellung” [Great German Art exhibition] in Munich, an annual show of art that the Nazis could instrumentalise for propaganda purposes. There it was acquired by the Austrian town of Wels.

The cast exhibited here, which was made after 1945, was acquired for the Sammlung GIERSCH in 2009. In 2010, the Museum Giersch staged a retrospective exhibition of Fritz Klimsch and August Gaul that also examined Klimsch’s complicity with the Nazi-controlled art business.

Fritz Klimsch (1870–1960)

In Wind und Sonne [In Wind and Sun]

1935–36

The sculpture In Wind und Sonne was created for an art competition held in the run-up to the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin. It was first presented to the public at the Paris Expo of 1937. Klimsch’s highly idealised female nudes accorded well with the Nazis’ understanding of art and were widely exhibited during the Nazi era, as well as being reproduced in numerous books and periodicals. The figures’ contemporary hairstyles anchored them in the viewers’ own present and helped make their idealised bodies seem not just realistic but realistically achievable. This insertion of idealised bodies into the viewers’ own visual world was also a subtle way of engendering support for the Nazis’ inhumane policy of destroying those bodies that deviated from their ideal. A cast of the statue sculpture In Wind und Sonne decorated the Reich Ministry of Public Education and Propaganda during the Nazi period.

The cast exhibited here was acquired by the Sammlung GIERSCH in 2006. In 2010, the Museum Giersch staged a retrospective exhibition of Fritz Klimsch and August Gaul that also examined Klimsch’s complicity with the Nazi-controlled art business.

Fritz Klimsch (1870–1960)

Frühling [Spring]

1925–26

Fritz Klimsch’s bronze is an allegory of spring in the form of a very young, petite woman with her arms raised. With its fluid lines and dynamic pose, the work emanates an atmosphere of youthfulness and vitality. The artist took his cues for it from Graeco-Roman sculpture. Klimsch’s embrace of this classical understanding of art since the beginning of his career helped ensure his popularity during the Nazi period. After all, Adolf Hitler himself had called for a “transition period,” during which the classical style of Antiquity might serve as a model. The Nazis therefore hailed Klimsch as a “Master of the Transition” and as a “Saviour of Form,” which in turn meant that he could exhibit and sell his works freely. Passages in Klimsch’s memoirs published in 1952 reveal that he was still thinking in Nazi-style racial categories even then. Thus he discourses on the skull shapes of German soldiers and describes General Alfred von Schlieffen as “one of the Nordic race.” He also expresses admiration for Contessa Rusconi-Jahn’s harmonious combination of “both races” and notes approvingly of Margarethe von Bonin that being of “good race” goes hand in hand with a “certain beauty […] in the expressiveness of the whole.”

The cast exhibited here was acquired by the Sammlung GIERSCH in 2006. In 2010, the Museum Giersch staged a retrospective exhibition of Fritz Klimsch and August Gaul that also examined Klimsch’s complicity with the Nazi-controlled art business.

Das Kooperationsprojekt »INTERIOR – Häuser mit Geschichte«

wird gefördert durch den Kulturfonds Frankfurt RheinMain.